The Park originally called The Parade and now named for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. has a unique history among Buffalo’s Olmsted parks, for it actually represents two distinct landscape designs by the firm, prepared for the Buffalo Board of Parks Commissioners some 25 years apart.

The original design was for a park called The Parade prepared in 1871 as part of Frederick Law Olmsted’s plan for the Buffalo park system. Olmsted, in the first design prepared for an American city encompassing a city wide park system, created three main parks and extended their influence throughout the community by a number of broad “parkways”. This park, which is now known as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Park, in contrast to both “The Front” (now called Front Park) which featured breathtaking views of the Niagara River and was intended as a setting for formal civic displays, sporting events and music performances; and to “The Park” (now known as Delaware Park) with its spacious display of landscape art and planned to be a welcome respite from the pressures and confinement of the city; was first called “The Parade” in keeping with Olmsted’s expectation that it would become the site of military drills and large gatherings of people. It occupied some of the highest ground in the city, and the plot chosen was generally flat and level, in contrast with the geography of the other two park grounds.

The Parade – 1870 to 1896

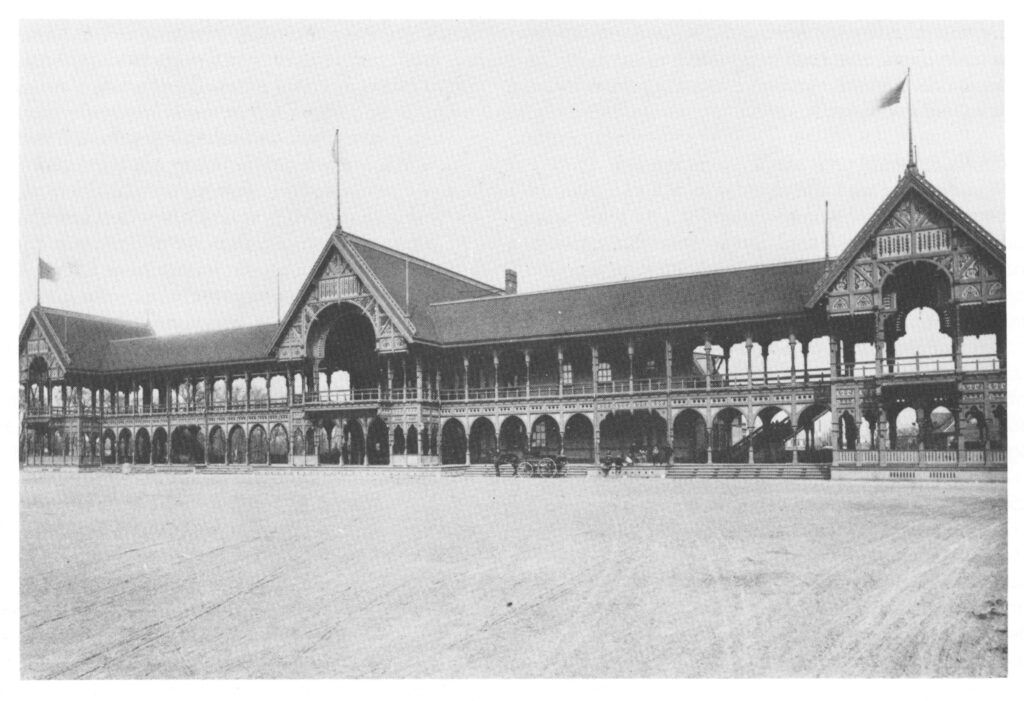

A truly spectacular public hall, the Parade House, was designed by Olmsted’s partner, Calvert Vaux, for the Parade. With plans were first drawn up in 1870, this wonderful structure was designed specifically to accommodate the large numbers of persons expected at the large public events anticipated to be held at the grounds of The Parade. The wood structure had a marvelous two-story series of porches and galleries. The building proper was 240 feet in depth, and 50 feet in width. and was 58 feet tall at the roof line. The porches or verandas were 15 feet wide, with enlargements to 28 feet in several places as viewing spots for activities on the parade ground. They stretched a full 250 feet across the structure at both its front and its rear, with extensions along the sides of the building, as well.

The first floor housed a restaurant 150 feet by 50 feet in size, along with a bar, private dining rooms, and comfort stations for men and women. The second floor held a grand ballroom, 210 feet long by 50 feet wide. At the rear of the building was a 128 foot tall tower with a viewing balcony. The tower portion also housed multi-level dwelling quarters for the concessionaire and his family. The verandas offered a fine site for viewing both the scenery and the military events. It was brightly painted in multiple colors.

Adjacent on one side was a barn and large carriage sheds between the Parade House and Best street. These accommodated visitors arriving by carriage. There was also street car service available within a short distance of the structure. On the opposite side, between the verandas, was a raised circular wooden dance floor. Completed in under one year, the Parade House opened to the public on the first of July, 1876, in time for the nation’s Centennial.

The Parade was distant from the city’s two armories, however. That inconvenience, as well as changes in military training needs subsequent to the Civil War, caused the park to be infrequently used as the large gathering space and parade ground for which it was originally conceived. Meanwhile, The Park, the largest of the new public grounds and the first of them to open, had totally captured the Buffalo community’s fancy. That resulted in considerable public pressure for its use as the site of public concerts, to both the detriment of The Parade … and to the chagrin of Olmsted.

The Parade became, in practice, more of a park site specific to its adjacent community. The Parade House also caused recurring problems with the larger community when the combination of musical entertainment, the alcoholic beverages served and the inviting nature of the space for loitering offended other parts of the community. The Parade House was well patronized, but mostly by the local ethnic German population rather than by the attendees of drills and maneuver or of larger popular concerts.

On 26 August 1877, slightly more that a year after its opening, a huge fire destroyed the edifice. Fortunately, the concessionaire and his family escaped the blaze unharmed, 14 persons had been asleep in the structure when the fire broke out. After the insurance claims were settled and after considerable discussion within the Park Board, plans were made for a replacement.

When rebuilt, the new Parade House was constructed on a smaller scale and from plans drawn by a local architect, Cyrus K. Porter, rather than re-using the original Vaux and Wisedell plans. The new structure while smaller, maintained a good deal of the detail of the original design. The facility again, however, was the source of constant tension with citizens who were offended by the occasionally raucous behavior of the patrons. The large drill ground proved to be difficult to maintain against the scars of paths worn across it by those who found it to be a very convenient neighborhood “shortcut” and also by teamsters who found that illegally cutting across the grounds with their conveyances was a very handy means of access between the southern and northern portions of Fillmore Avenue (which at that time did not connect, the northern and southern portions of it terminating at the park). In 1886, the Park Board capitulated, and Fillmore avenue was extended across the grounds. The National Guard, however, ceased use of the grounds in 1893.

A New Design As Humboldt Park – 1896 to 1977

Due to the altered focus in the utilization of The Parade, in 1896 the Park Commissioners decided to task the Olmsted firm to prepare a completely new design for the park, more in accordance with what they felt to be contemporary community needs. Olmsted was incensed that his original plan was to be abandoned, and suggested that the park be divided into building lots rather than altered. Heeding more prudent counsel, the Olmsted firm (which was now headed by Olmsted’s son, John) prepared a new park plan which retained some of the more successful features, including the Parade House, but replacing the drill ground with a set of formal water features: a large circular fountain, a rectangular basin for aquatic plants, and a huge wading pool of more than 500 feet in diameter. The wading pool was also to be used for ice skating during the winter months.

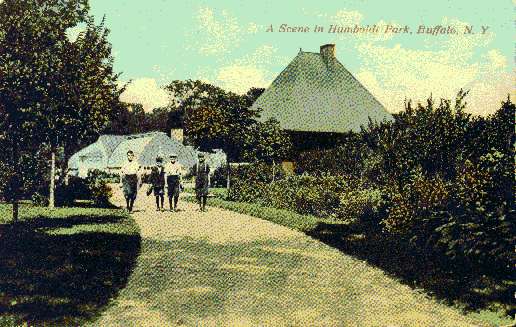

Adjacent to the Parade House, a picnic ground was laid out in the northeastern section of the park. Also included were provisions for a conservatory and flower gardens, a bandstand and a playground outfitted with gymnastic apparatus. The Park Board changed the name of the park to Humboldt Park (after the name of the parkway stretching between it and Delaware Park) in reflection of its altered character.

An elaborate granite bandstand, identical to one erected simultaneously at the Front, was constructed in Humboldt Park in 1898. It was needed because the northern veranda of the Parade House had been removed the previous year, leaving no location for use a park bandstand. The proposed conservatory, was not constructed until 1910; the bear pits and most of the proposed playground infrastructure were never installed.

Finally, in 1903, the transformation of the park from its original plan was completed when the Park Board determined to resolve the recurring tensions caused by the Parade House and its use for the sale of light alcoholic refreshments by the demolition of the once grand structure and its replacement with a small and simple park shelter.

This change required further revisions to the grounds, and the Olmsted firm drew up these modifications to the southeastern portion of the park in 1904, changing the focus of the grounds to be less city-wide and more oriented to its surrounding neighborhood. The new park shelter, designed by Buffalo architect Robert A. Wallace with a unique “Swiss chalet” style and roofline, reflected this change. The Olmsted firm was engaged to redraw plans for that segment of the park to account for the Parade House removal and the construction of the new shelter, as well as siting for the intended building of the conservatory. In 1910, as mentioned, a new Lord & Burnham conservatory was constructed, completing the construction of the Humboldt Park grounds.

Subsequent modifications to the park were accomplished without the guidance of the Olmsted firm. They also proceeded without the oversight of the Park Board, their function having been transferred to a department of public buildings and parks when a new city charter was adopted in 1915. In 1925, the new home of the Buffalo Museum of Science, designed by by the firm of Esenwein & Johnson, architects for a number of prominent Buffalo structures (including the General Electric building at the junction of Sycamore, Huron and Washington streets and the Temple of Music at the Pan-American Exhibition) was placed at the head of Humboldt Parkway within the park. It opened to the public in 1929. That same year the Chopin Singing Society donated a bust of Chopin which was placed in front of the Science Museum (and subsequently moved to Symphony Circle). The present brick casino building was constructed between the lily pond and the wading pool in 1926. The building boom continued, to the detriment of the park’s Olmsted heritage. In 1938, serious consideration was given to constructing the city’s new music hall in the park at the back of the Science Museum, near the Herman Street entrance. Fortunately that did not occur, and instead the present Kleinhan’s Music Hall was constructed on Porter Avenue at Symphony Circle.

Changing times and lack of use resulted in the demolition of the bandstand in 1950. In 1956, the first of Buffalo’s refrigerated outdoor artificial ice rinks was constructed on the site of the lily basin. The same year, it was proposed that a new School 24 and Junior High School be constructed in the park. That proposal was defeated, but the idea of taking park land for school construction would surface again.

In 1960, a massive negative change impacted the park when the city’s new arterial highway system cut a swath through old neighborhoods. The eight rows of stately trees in 200 foot wide Humboldt Parkway were cut down for the construction of the Kensington expressway in April of that year, and what had been a broad and more than three mile long extension of parkland stretching all the way to Delaware Park became instead a concrete highway separating neighborhoods on either side. All that remains today of the former crowning jewel of Buffalo’s parkways is a tiny parcel between Northampton Street and the unused staircase leading to the former front entrance of the Science Museum, the spot where Chopin’s bust had been placed. (Chopin, now spared the sad view north along the parkway’s former path, has had his bust was relocated to Symphony Circle (originally, “The Circle”), adjacent to Kleinhan’s Music Hall.) Additional changes at the park followed, many caused by the total destruction of Humboldt Parkway in the 1960s by the Kensington Expressway. The new four lane sunken high-speed thoroughfare severed the connection between this park and the rest of the Olmsted-designed parks. What was part of a grand city-wide greenspace came to be viewed as just another local city park. The fountain was replaced by a basketball courts and a large group of spectator bleachers. The lily pool was partly filled and a wading pool was constructed at its eastern end. The wading pool was partially filled, and transformed into a smaller circular concrete “spray pool”, while its grand dimensions and grassy banks were retained.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Park – 1977 – Present

On January 25, 1977 the park was renamed in memory of Dr. Martin Luther King. Jr, an honor which was delayed by one year from its first proposal due to political factions within the city council. Subsequent to the renaming, an eight foot bronze bust of Dr. King was placed in the park, near the park shelter house. The bust stands on a sloping mound, eight feet high at its center, facing a stone plaza shielded from the traffic of Fillmore Avenue by a screen of evergreen trees. This siting required a number of changes to the landscaping in the immediate vicinity. It was formally unveiled in October 1983. The bust has been criticized by some for not being a direct likeness of Dr. King, but its sculptor, John Wilson, specifically intended the work as an interpretation “which would sum up the larger-than-life ideas” of Dr. King and capture his “inner meaning” rather than be simply a life-like representation.

The following year, 1984, a major alteration to the Olmsted design of the park was proposed by the Buffalo Board of Education when it announced plans to construct the city’s new Science Magnet School within the park, adjacent to the Science Museum. A coalition of neighborhood residents, parents, environmentalists and preservationists, led by the Buffalo Friends of Olmsted Parks (now, The Buffalo Parks Conservancy), was formed in opposition to the plan. Rejecting alternatives to the site, the Board of Education persisted in placing the school in the park. After a lengthy and bitter controversy, including an unsuccessful lawsuit brought by the coalition, in 1986 the Board won the right to build the school. Opening in 1990, and designed by the firm of Steiglitz and Steiglitz, the Science Magnet School has received recognition for its design. At the same time, it must be seen as a massive and negative impact on the historic and artistic landscape design of Martin Luther King park.

A movement to restore the large wading pool made progress in the early 1990’s, as community leaders and park neighbors succeeded in designating funds for its restoration. The realities of modern economies and of changing laws regarding safety, liability and water purity, however, blocked the successful return of Martin Luther King Park’s central feature to its former glory. A portion of the money was used in 1992 to establish a new rectangular children’s wading pool on the site of the former water plant basin and neglected ice rink, and to clean and partially refurbish the casino. However, decisions on how best to restore or reinterpret the main pool were elusive. A plan to turn it into a fishing pond was begun, then halted. A reflecting pool was proposed, but was unfeasible due to modern regulatory and safety concerns. The solution which was finally reached was to retain the full footprint of the wading pool, with the installation of a multi-jet spray pad to continue its purpose as a most welcome summer relief from the heat for neighborhood children. Alas, that installation proved to be an on-going maintenance challenge. Finally, beginning in 2012, a second reconstruction of the central basin expanded the splash pool with 300 jet sprays up to fifteen feet in height, computer controlled, which covers about one-half of the 500′ basin area. While in summertime it serves as a splash pool, it can also be flooded in the fall and spring to serve as a passive 5 acre reflective pool. In winter, temperature conditions permitting, the flooded basin is able to be used as an ice-skating facility. It opened for first use on June 1, 2013.

Although considerably altered by the removal of the Parade House and the construction of the several major newer structures, most recently by the building of the Science Magnet School, Martin Luther King, Jr. Park today largely continues the 1896 design. It is a unique park in the city’s Olmsted system. It not only represents two separate Olmsted designs, but also a combined city-wide and local orientation. It bears the scars brought by the pressure of intrusive construction and the neglect resulting from depleted city finances, yet it clearly evidences of the love and respect its neighbors show its grounds. It is home to what is probably the saddest view in the Buffalo park system: that tiny remaining plot of once-grand Humboldt Parkway as one gazes down the concrete path of the Kensington Expressway. The bright side of that is the present fight of the East Side Parkways Coalition to force the removal of the expressway, returning it to the parkway it once was.

260101